Ethics in Education?

Ever given any thought to ethics or how to teach it during your professional career? Ever given any thought to ethical standards outside your profession? These questions have persistently surfaced for me over the past few years and so I decided to consider them in relation to tourism, especially to places of historical or cultural significance, and the urgent need for education about ethics.

My bushwalking pal is a budding fiction writer and she had often spoken of her admiration for MIchael Oondatje’s The English Patient, which she considers great prose. I finally admitted to never having read the book nor seen the movie. With some hesitation she lent me her copy, first of the book, then the dvd.

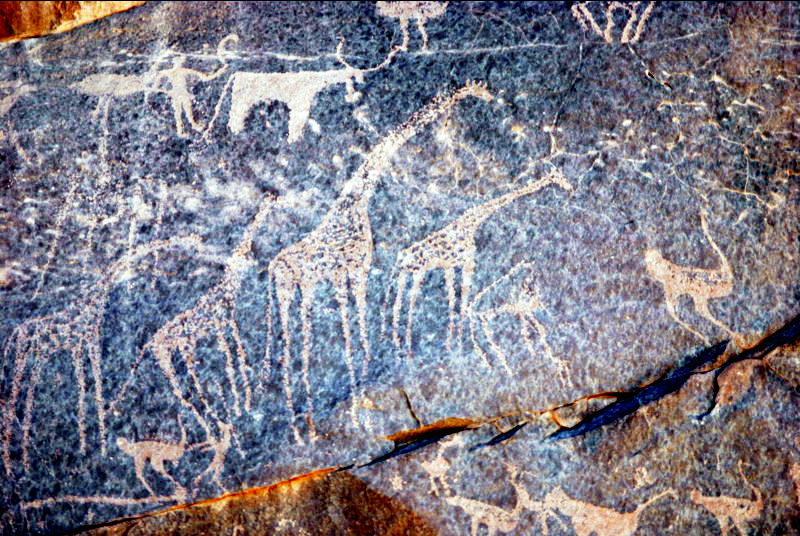

As a former Archaeology and Egyptology student I was fascinated by the location. A Google search revealed it did exist but to purchase a copy of Lazio Almasy’s ‘The Unknown Sahara’ stretched the budget of my interest a little too far. However, the website of The Bradshaw Foundation covers the rock art of the Gilf Kebir, and this was enough to satisfy me.

Then, horrifically from my perspective of ethics, further research revealed that parts of the cave have been irreversibly damaged by ‘visitors’, especially since the film was released in 1996. The horrors include the removal of parts of the paintings and graffiti. A restoration project by archaeologists has included education of guides and the local community about the value of the cave to prevent further damage.

Yet still, who are these ‘visitors’ who have stolen irreplaceable rock art and what do they hope to gain from it? This thought led me to further reflection on the book and the film. The film had a powerful impact on my sensibilities and left me with a feeling of the devastation caused by betrayal. In one sense the movie led to the betrayal of the site itself, and the subsequent damage by tourism.

Another consequence of the rise of tourism shocked my small family when we visited Kbal Spean in Cambodia many years ago in 2004. The trail to this amazing site, a climb up a steep hillside, had only just opened according to our guide. We needed to stay on the track and follow the guide carefully as the rest of the hillside had not been cleared of landmines, we were warned.

The site, a river and series of cascades and waterfalls is known as the River of a Thousand Lingams, because of the many neat rows of Siva lingams carved into the sandstone over which the river flows. There are also many fine carvings of Hindu deities, some dating from as early as the 11th to the 14th centuries.

Then, to our dismay, we noticed a gaping wound of freshly exposed sandstone behind one of the cascades. Our guide shook his head disapprovingly “Only one night after it open, before police post here.”

In a country known for its corruption, it did not surprise us that a carving of Vishnu and Lakshmi had been shaved off and delivered to a collector somewhere in the world, paying its way through a series of ‘donations’ to those who assured its safe passage. Again, who are these collectors and ultimately, what do they hope to gain from having a priceless carving in their possession?

Museums around the world possess many such objects and fragments, and justify their ownership, from the perspective of the survival of these artefacts. Should they be returned to their countries of origin? Who owns the past, after all? How do we as a world community establish ethical and responsible tourism? Do we all need bucket lists?

Most importantly, in a professional role that is increasing under pressure for further curriculum and administrative requirements, should we and how do we, teach ethical and responsible behaviour in our students? Will these students, as adults, behave responsibly as global citizens if they travel the world?

The questions just keep rolling out, so please let me know your thoughts.